Museum ‘Touch’ Experience for Blind and Partially Sighted to Benefit Everyone

By: Amy Cheng

The blind and people with low vision may soon be able to experience museums in a different way.

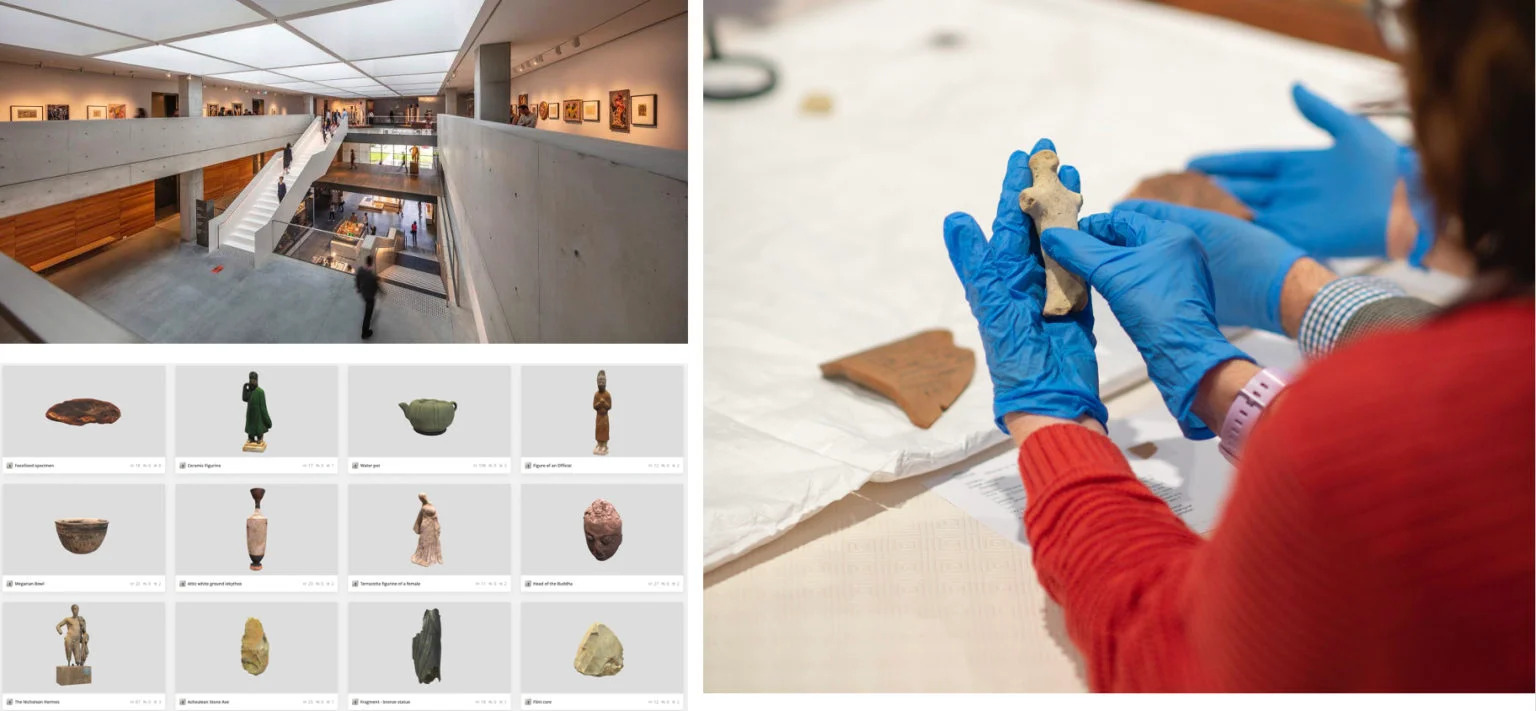

New research led by the University of Sydney is proposing the design of “touch models” to enhance the museum experience for everyone.

The research is being funded by 2023 Alastair Swayn Foundation International Grant and is a collaboration between the Chau Chak Wing Museum, the University of Sydney’s Faculty of Medicine and Health Media Lab and the Institute for the Blind and the Partially Sighted in Denmark.

Museum objects are often behind barriers to protect them from being damaged, but these models will be tactile representations on display for people to engage with.

Dr Dagmar Reinhardt, lead researcher and Associate Professor of Architecture, said the focus for her and her team are objects that would normally be out of reach of the public.

Museum objects are often behind barriers to protect them from being damaged, but these models will be tactile representations on display for people to engage with.

“The whole point is really to make a representation of what sits behind glass so that it exists in the first place,” she said.

“We are really interested in the representations of objects and things that can be touched that either would be too dangerous or too vulnerable or too old or too precious.”

The idea for the research came from different places but a big influence was her father, who has low vision.

“He has been very badly sighted all his life… and then he had cataracts and had a couple of operations,” Dr Reinhardt said.

“I think he has like 0.5 per cent or so (vision), so he can see something in the left lower corner of his eye at moments and he can distinguish shadows.”

With her background in architecture, she will help design the museum space and experience for the benefit of the blind and people with low vision and help “make a better world”.

“I design it from when you enter the museum through the website, where you get that first information,” Dr Reinhardt said.

“Then you enter physically the museum so, at the entrance of the museum, something must be displayed and then you move into the exhibition and go into sort of the finer details.”

Experiencing the world differently

The museum experience mostly benefits those with sight, Dr Reinhardt said.

“But if you’re blind, nothing exists because it’s behind glass or behind a border, so… nothing can be touched.

“For someone who’s very deeply embedded in the world, wants to touch things in order to understand, that’s very important.

“If you can touch it, there’s a benefit for all, so it’s a museum for all, it’s not only for the blind and partially sighted.”

She said vision enables us to obtain information quickly.

“When we are seeing, we are very fast – we see, we scan, we look over something and then we think we understand it – but to really go deeper, you need to look at the details.

“Our way of seeing and perceiving information is top down, but for someone who’s blind or partially sighted, that is bottom up – they touch details first and then they collate these details into an image.”

Dr Reinhardt is often amazed at how they experience the world.

“There’s a world out there that we don’t understand, where people who are touch gifted, they understand that much better,” she said.

“They have a very different spectrum of understanding how the world works and I’m completely and deeply in awe of that because they hear in a different way, and they touch and have sensations on their fingertips in a very different way.

“The people that I talked to were touch experts; they were specialists.”

How touch models will work

A touch model on its own will not be sufficient to give someone the whole experience of an object, Dr Reinhardt said.

The models will be accompanied by diagrams that can be touched or other materials that provide additional information, such as maps, along with an audio and Braille component.

“(It will) allow you to have a conversation around information about the world in general.”

However, there are certain challenges to creating touch models, she said.

“It’s a trial-and-error thing; some things that I find particularly interesting don’t work at all if you do touch.

“I’ve been trying to translate motion, like an animal in motion, and that’s difficult because that’s something that you see but how do you display that?”

Working with the blind and low-vision community

Dr Reinhardt has been working with the Sydney Braille Forum, Vision Australia and Viscon to present workshops to small groups of about 10 people.

“I lay the objects out on a table and people sit around the table and then I hand the objects over to them with a bit of a background and narrative, it’s very one on one,” she said.

“People love it… when that smile comes out, there’s always a moment when people really, really smile when they touch something; it’s amazing.”

Looking to the future

Dr Reinhardt is hopeful that these touch models will soon be available in museums in the next three or so years.

Once her team has completed their research, it will be uploaded onto an online platform as a resource for people around the world.

The team is planning on doing a test run with the touch models with a pop-up exhibition during the school holidays in January 2024.

Article supplied with thanks to Hope Media.

Feature image: Supplied